Motivation

Having committed to writing a blog about both Meteor and running (and even chosen the blog title on that basis), I find myself compelled to produce a post about the latter, despite the fact that I’m unable to do very much of it at present. So, to begin, a disclaimer:

- I am currently injured, and as upset about it as any runner tends to be.

- Apart from being a running enthusiast, there’s no reason at all why I should have any idea what I’m talking about; I’m not a physio, coach, doctor or anybody else with vaguely relevant qualifications.

- This is hugely self-indulgent, but hopefully cathartic.

That said, my recent experience with heart-rate training, which may or may not have something to do with my current injury, may at least provides some material for discussion. The question I’m trying to answer is: if a runner is going to commit to a heart rate training regime, do they actually need to practise running slowly first?

Honestly, it’s not as easy as it sounds.

Heart Rate Training: the Principle

Without dwelling on the scientific and psychological rationale behind training with a heart rate monitor, which is amply discussed elsewhere, suffice to focus on the observation that, left to their own devices, athletes almost uniformly tend to perform easy sessions at too high an intensity and hard sessions at too low an intensity for optimal benefit - i.e. they revert to the mean. Heart rate monitoring acts as an effective aid in this respect as it provides immediate feedback on the runner’s failure to remain at the targeted training intensity, often accompanied by an annoying beepy noise, which the runner in question will no doubt be incentivised to silence with their renewed compliance.

Thanks to regular Thursday sessions being dragged around Parliament Hill track by Tom Craggs with the rest of the Mornington Chasers, the peer pressure required to run harder than I would usually contemplate alone was being applied with sufficient regularity to leave me confident that the hard days were genuinely just that, but I wasn’t sure the same could be said about easy days, which tended to be somewhat laissez-faire. With the Frankfurt marathon coming up in October and consequent necessity to increase weekly mileage, the prospect of applying a scientific approach to the easy runs seemed appealing. As, frankly, did spending an unnecessary amount of money on a smart new running watch.

Garmin Forerunner 620

If you’re looking for a good way to spend more than £250 and justify it by pretending that your running performance will be magically transformed, I can offer no better suggestion than the Garmin Forerunner 620. Of course, it’s the training that makes you faster and the watch doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with it, but for those of us who want something on our wrists that looks smart and tells us our vertical oscillation, this is the gadget we’ve been waiting for. Heart Rate, Race time predictor, VO2 Max estimator, Recovery Advisor, Ground Contact Time and Cadence (more of that later) are all provided, along with the usual pace and distance data.

Running very slowly is difficult

I’ll leave out the details surrounding calibration, and cut to the chase: how does it feel to do as instructed and run in heart rate zone two? For me, very, very slow, that’s how. Any slight incline prompts a series of beeps from the watch, as does thirty seconds not spent actively concentrating on running slowly. There are encouraging aspects to this observation: certainly, cycling at the same heart rate doesn’t feel anything like as comfortable, suggesting my physiology has adapted to running to at least some extent. But the fact remains: running this slowly is genuinely difficult.

My Running Form (Part I)

Now I am not the world’s greatest runner, or my city’s greatest runner, or my club’s greatest runner. The number of runners I would need to be among to represent the greatest would be really very small. However, the gradual assimilation of advice from coaches and reputable running publications, along with quite a lot of practice, has at least left me with a running style which is pretty fluid and efficient, with a fore-foot strike, an upright posture and a relatively fast cadence (thanks, coach Craggs). It’s not perfect, but it’s pretty solid:

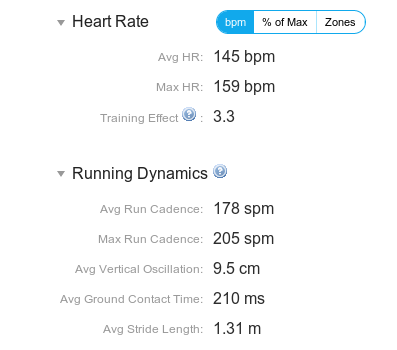

My shiny new toy provided some encouraging statistics to back this up: a healthy cadence of around 185spm at tempo pace, ground contact time hovering just above 200ms (which, supposedly, is good) and vertical oscillation generally below 10cm (average, but not terrible).

Unfortunately, all that was abandoned in spectacular fashion when I started to limit my heart-rate.

My Running Form (Part II)

How does one reduce effort, and therefore heart rate, without compromising running form? To an extent, the strategy of reducing stride length and maintaining everything else seems logical, until one actually tries to do it. Fairly quickly you end up replicating the sort of tip-toeing neuro-muscular warm-up exercise that’s ideal before a track session, but feels (and probably looks) ridiculous when you’re trying to run round the park and, crucially, doesn’t actually get your heart-rate into the designated zone. It’s probably perfectly possible to run 8m30s miles at 180spm, but I don’t seem to be able to do it.

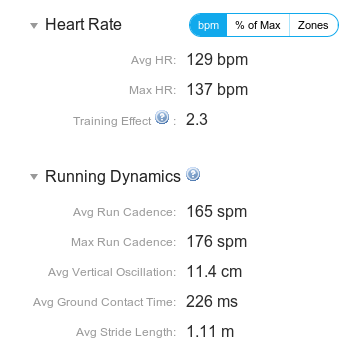

So, the cadence inevitably drops. And drops. And drops. And I end up loping up and down in a fashion that feels ungainly and has the statistics to back it up: ground contact time way up, cadence way down and, most worryingly, vertical oscillation which the Garmin now classes as bright red (for which you should read “awful”). Whether the received wisdom on the consequences of such a dramatic change in running form is correct or not, there is strong evidence that it’s not a great idea.

During the three weeks over which I persevered with this regime, I grew to understand and appreciate the physiological rationale behind heart rate training: whilst self-assessment is no way to judge a training plan, there’s no doubt that I was consistently fresher and less fatigued than during previous periods of heavy-ish training, despite logging more miles per week (40-50 as opposed to 30-40). Unfortunately, my lower legs also began to hurt in a way that they hadn’t for several years, with the pain in my left shin getting progressively worse until one long run left me struggling to walk down stairs the following day. That was three weeks ago.

The Big Question

As I suggested earlier, I’m currently injured - awaiting the results of an x-ray but comprehensively condemned to the pool and gym for the foreseeable future either way. It would be absurdly unscientific to link cause with effect on a sample size of one, particularly when it’s my own body,and even if the change in training was responsible, it was my own failure to adapt my running style sufficiently, or indeed abandon the project before I got injured. Nevertheless, it does make me wonder.

Leaving aside the watch, the statistics and most of the science, is it advisable, or even possible, to run a lot slower than your natural pace? If the answer is yes, shouldn’t there also be some advice on how? For cyclists, turning down the intensity is a straightforward matter of gearing, but running doesn’t really work like that.

There are all sorts of articles out there advising us on how to run quicker - is it time we had one teaching us how to run slowly?